Trying-Out: “The removal of whale oil by boiling strips of blubber harvested by whales; also known as “flensing’.”

The Trying-Out of Moby Dick by Howard P. Vincent, is a scholarly study of whaling sources of Moby-Dick with an “account of its composition, and suggestions concerning interpretation and meaning.” I found an annotated First Edition (1949, Houghton Mifflin) in the “Whalemen’s Shipping List” bookshop, located next to the Seamen’s Bethel in New Bedford, MA, during a whaling adventure last Spring. [see post]

The origin of Melville’s whaling story came from the journals of the Essex of Nantucket, which was rammed and sunken by a gigantic sperm whale in the Pacific Ocean in November,1820. After a 4-year whaling voyage of his own, Melville would read the account of Owen Chase who survived the sinking of the Essex and write about the incident in Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex.

In The Trying-Out, Vincent explores not only the evolution from Melville’s point of view, but also the rewriting of Moby-Dick before its publication and the influence that Melville’s new friendship with Hawthorne had on his complete shift in philosophy.

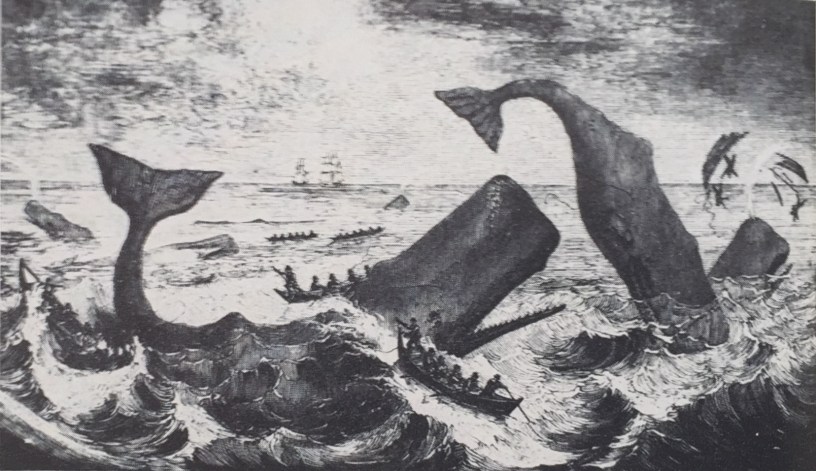

A large portion of The Trying-Out is devoted to the Cetological sources and basically everything you would want to know about whaling. Trying-Out also includes illustrations of original drawings of whales by Cuvier (that Melville probably used to reference his whale) and the logbook of his own whaling voyage on the Acushnet. Cool, cool, cool!

According to Vincent, “In order to be true to external nature, a poet must first of all be true to his own nature…be it fashionable or unfashionable, great or small, virtuous or venal” (Spender, 28).

In Trying-Out, Vincent states that, in addition to many voyages on whaling ships, Melville sought most of his documentary evidence of the sperm whale from two sources: Beale’s Natural History of the Sperm Whale and Cuvier’s De l’histoire naturelle des cetaces, ou recueil et examen des faits don’t se compse l’histoire naturelle de ces animaux, (Paris 1836).

To insure accuracy for Moby-Dick Melville studied Thomas Beale’s famous Natural History of the Sperm Whale which gives the chapters on whaling (most of the book!) authenticity. He did not reference much of Cuvier’s L’Histoire as it was written in French. [literary intersection: I became familiar with Cuvier’s writings on nature when I lived in Paris near the Jardin des Plantes, (rue Cuvier), a twenty-eight hectares (about 70 acres) wonderland of: 4,500 different species of plants, an Alpine garden with 3,000 species of world-wide representation, a labyrinth from 1739, a Ménagerie of over 1,000 animals including an elephant and kangaroos, and five massive museums (Musée National d’Histoire, the Grand Galerie de l’Evolution, the Mineralogy Museum, the Paleontology Museum and the Entomology Museum). See blog post:

Most importantly, Melville writes about what really interests him. Vincent puts Melville’s vision of whaling in the same class as other great artists: Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Handel, Beethoven, Homer, Dante, and Milton.

Originally, Melville had not planned to include the intellectual voyage as a part of his “whaling voyage.” (34) After reading Mosses from an Old Manse by Nathaniel Hawthorne, however, this changed. Melville began to rewrite Moby Dick and would include the theme of evil as a core of life: “an ideal artist must keep his faith in himself while the incredulous world assails him with its utter disbelief,” Melville would express to his comrades. Melville and Hawthorne would subsequently meet a form a kindred friendship as revealed in their many letters over the next few years.

According to Harrison Hayford in “Melville and Hawthorne”, there were at least nine known meetings during this friendship. Hawthorne also gave many books to Melville from his personal library. Melville fleshed out his ideas with Hawthorne which led to mold the metaphysics of Moby-Dick (39). [Melville would dedicate his great whaling epic to Hawthorne “In Token of my Admiration for his Genius.”]

While working on the revision of Moby-Dick, Melville had a “sea-feeling” while living in a Berkshire, snow-covered retreat: “I look out of the window in the morning when I rise as I would out of a port-hole of a ship in the Atlantic.” As Melville was working 5-6 hours a day, he was now writing from the “depths of his mind and heart not tapped before…his mind was overflowing; his heart was full of futurity” according to his letters of his daily routine (41). We later will see this same vigor in Ahab concerning his quest of the great White Whale!

Melville finished the rewriting of his novel and had it ready for publication on 14 November, 1851. Melville uses many themes in Moby-Dick. We see an Homeric theme, Man against Nature as well as Plato’s theme: The richness of his wandering past fused with the reflective wisdom of the thoughtful present. This combines two worlds and two sets of experiences: material and immaterial, physical and metaphysical (51). Vincent also points out some of the main themes: travel, economics, zoology, intellectual history, metaphysics, and the mystery of the avenging dream (52).

Vincent’s book is divided into two main sections: the Narrative and the Cetological Center. This blog is concerned with the narrative: the lonely wanderer, Ishmael, on an Odyssean faring. According to Vincent, “[Ishmael] The Narrator of story begins on a lonely journey to New Bedford which ends with a lonely journey of being the only survivor of ship’s sinking. Ishmael is Everyman. Ishmael is Melville; Ishmael is any man, anywhere, confronted with the flux of circumstance and with the chaos in his being.”

Ishmael is an amalgamation of the self-assertive Ahab, the good sense and sobriety of Starbuck, the animal grace and undivided mind of Queeque, the frivolity of Flask, of Fedallah and of Pip. These are all phases of Ishmael’s total self-personified (56).

It is not lost on the reader that there are no concrete details of Ishmael-color of eyes or hair, size, etc. He remains nebulous. Ishmael is monistic; Ahab and crew are multiple personality. Moby-Dick is a study of both with psychological phase of the problem of One and the Many.

Vincent compare Ishmael’s narrative of “aloneness” to Keat’s famous poem La Belle Dame Sans Merci. As my literary worlds so often intersect, I recently became familiar with this poem while researching Keats for a Lit course that I audited. In La Belle Dame, a fairy condemns a knight to an unpleasant fate after she seduces him with her eyes and singing. The knight, alone in his blindness, begins a quest to find love just as Ahab begins a quest to find the Great White. Both end in tragedy. [note: only the title is French; the poem was composed in English. Keats was inspired for the title and premise from the 15th-century poem of the same name by Alain Chartier]

Vincent also includes in his narrative section that the inspiration of Melville in writing Moby-Dick came shortly after the newly formed United States. The United States was a symbol of individual freedom, like Ishmael, Ahab and Moby (62).

[ He also includes the libertarian philosophy of Locke and the French Encyclopedists of that time. See my blog post: “The Quest for Moby Dick: the Philosophical View of Whales” See Post]

As Vincent concludes, ““Melville learned the lesson of looking; to gather his emotions around concrete objects, not to merely see a thing, not merely to describe a thing but to become the thing, not merely to hover above it like an atmosphere…to create from the thing and from the contemplation of it a third and independent thing, a work of art.”

I will review Vincent’s “Cetological Center” of The Trying-Out in my next blog post along with the companion reading of Thomas Beale’s Natural History of the Sperm Whale and Cuvier’s De l’histoire naturelle des cetaces, ou recueil et examen des faits don’t se compse l’histoire naturelle de ces animaux, (Paris 1836). So excited!!!

Copyright 2019 by Robyn Lowrie. May be quoted in part or full only with attribution to Robyn Lowrie (www.frenchquest.com)

Work Cited

Howard P. Vincent. The Trying-Out of Moby-Dick. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin. 1949