How can one be an admirer of Aldous Huxley’s works without ever having read his iconic Brave New World? I am here to attest that one can!

I prefer non-fiction to fiction. I like to do deep-dives into an Author’s life and biography before I consider their works. In fact, I became a Huxleyan after reading his lesser-known work of non-fiction, Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow [see post]. Tomorrow is a materialistic, naturalistic, and behavioristic outlook of the human spirit which Huxley sees as distinct from the body.

He states, “for, in comparison, the capacity of the spirit is limitless and subject to profound modification; the spirit is the result of all experience” (Tomorrow, “The Education of an Amphibian”, 2). Huxley basis his views on “modern psychology” (mid-century!) to the individual sense of oneness. The capacity of the spirit gives a oneness to the obvious diversity within the individual man.

Tomorrow was a follow-up read after Paul Valery’s Alphabet and Man in the Mirror which carries the same themes of self-analysis. “As in water face reflects face, So the heart of man reflects man”(Proverbs 27:29)!

Obviously, I do believe that one cannot fully know and appreciate an Author separate from his works-rest assured!

For this blog, I am considering the Critical essay of Keith M. May on the works of Aldous Huxley (1972 Harper & Row). I also have checked out Huxley’s Crome Yellow, Eyeless in Gaza, and Point Counter Point from my university library to become more familiar with his novels—May, however, states that calling Huxley’s works “novels” is incorrect. Huxley’s works should be called works of “fiction” instead of “novels” May avers. We shall see about that! ( Brave New World is at least considered “Menippean satire” by May—whatever that is). For this blog post, I will reference Crome Yellow.

Aldous Huxley’s Background

Before becoming a prolific writer, Huxley was informed of music, architecture, painting. May states that these forerunners aided Huxley in making fiction his own—it helped him to be original, lucid, and repetitious (Aldous, 5). What Huxley is saying, directly or through his characters is seldom in doubt, which is precisely what now draws me to his novels.

According to May, “Huxley’s fiction aims at generalizing the philosopher and the artist. He normally causes his characters, his language, his plots, and his structures to signify richly rather than reproduce the exact multifariousness of personal experience”(14). We can anticipate the element of surprise in his characters. Huxley can show either the rightness or wrongness of their attitudes in his novels. In this way, he avoids caricatures, which is my preference.

Huxley gives occasions on which a character’s train of thought is given and he or she is ‘seen’ thinking, ‘seen’ feeling, as when Denis Stone is standing on the parapet in Crome Yellow and thinking of suicide or in Eyeless in Gaza in which Helen Ledwidge has a distinctive face, voice, and family background, a performer of good deeds, and not just a physical presence.

As Huxley enjoyed the study of psychology and felt it was an essential element his works of fiction, he was particularly interested in the classification of human beings, in the Galtonian, Jungian, and Sheldonian categories.

He also admired that talent of European artists and authors. He referenced the works of Italian artists and 19th century French Literature, (which is in my wheelhouse!) in his novels. For example, In Crome, we meet Mr. Barbecue-Smith, “a man with a very large head and no neck… as Balzac described in Louis Lambert that all the world’s great men have been marked by the same peculiarity…the shorter the neck, the more closely the head and the heart”(Crome, 51).

Huxley gives a nod to Caravaggio’s “portentous achievements” in Call of Matthew, Peter Crucified, The Lute Players, and Magdalen” (Crome, 111).

May shows that Huxley regularly portrayed hedonists, or cynics because he wished to question the validity of their responses. I like this. Instead of this being left up to the reader to decide, Huxley lays it out clearly. Huxley’s characters often started with his own observations of life. This is true of most Authors who fill their character’s dialogues with their own musings and recollections of family, friends, schoolmates, Teachers, etc. Art imitates life, n’est-ce pas?

Crome Yellow (1922)

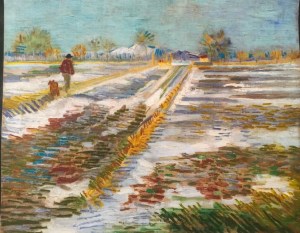

I must confess that the first thing that drew me to Crome Yellow was the color of the novel. It is actually more of a cadmium yellow, but it is still in my life palate! I accent my home, wardrobe, and now my books in this lovely hue. When I think of the color Chrome yellow, I think of Van Gogh’s wheat fields and sunlight landscapes from the south of France!

Not much happens in “Crome”, this sleepy little English Country House set in the early 1920’s. Even though it is not mentioned much in Huxley’s first novel, the world was recovering from World War I. Many towns who lost their men to the war were trying to rebuild. The protagonist in Crome, Denis Stone, observes: “You can’t expect an ordinary adult man, like myself, to be much moved by the story of his spiritual troubles…After all, even in England, even in Germany and Russia, there are more adults than adolescents” (30).

May states that Crome Yellow displays the great literary tact and awareness of Huxley’s capacities through a series of anecdotes, short stories, vignettes and essays by various means fused into a whole (27).

I love the setting of the Crome country-house in this story told in the most simple of events: dancing to a pianola, sitting for a portrait, tea on the lawn, the scent of lavender, evening shadows on the corn, the everyday incidents of a country household in the summer.

Huxley spent his childhood in similar surroundings. His brother Sir Julian Huxley said of his brother Aldous, “As a child, he spent a good deal of his time just sitting quietly, contemplating the strangeness of things”(33). This contemplation perhaps led to his remarkable strong visual understanding in descriptions of scenery, like those of a landscape painter (again I think of Van Gogh) as well as his giftedness in the use of dialogue in “bringing out the character”(35).

Whenever Huxley wishes to convey the workings of the mind, according to May, he uses indirect speech. This style was common in the early 1920’s, pre-Joycean techniques, which rendered states of consciousness at hand. “There is an ironic ambiguity which disappears only when a character is intelligent enough to be approved of by the author”(37). May asserts that the reader of Crome Yellow, therefore, must stay vigilant not to mistake Huxley’s dialogue of something perfectly serious for “amusing reading”. Crome Yellow has been called ‘a radiant conversation-piece’; for example, Pricilla Wimbush speaks in short sentences, or a succession of spasmodic phrases and clauses, conveying rather mannish jollity, while the speech of Henry Wimbush is always dignified, rational, and grammatical(38).

There might be harmony in this English hamlet setting, however, the world continues to be at war; we find in the early chapter, Germany and Austria are at war with England, France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, and Portugal (86). “As for the war having come to an end–why, that of course was illusory…It was still going on, smouldering away in Silesia, in Ireland, in Anatolia, in Egypt and India… Japan had boycotted the Chinese, and the genuine Armageddon might soon begin” (90). Fast forward to 1939, WWII.

I like that we find in this sleepy little town, much discussion of world events and history. Imagine sitting in your backyard, sipping lemonade, and your neighbor queries: “When I meet someone for the first time, I ask myself this question: Given the Caesarean environment, which of the Caesars would this person resemble—Julius, Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero?”(157). Or perhaps one of your neighbors breaks into a French melody as Ivor serenades:

Phillis plus avare que tendre,

Ne gagnant rien à refuser,

Un jour exigea à Silvandre

Trente moutons pour un baiser (165).

My favorite part of Crome is the extensive library which has been cultivated by the estate owners for centuries. Thank you, Huxley, for including this in your tale! Henry Wimbush recounts the first books acquired by Sir Fernando which include: Boethius’ Consolation of Music, Logic, Theology, and Philosophy (cool, cool, cool. I must have this–it is very rare and expensive to purchase, alas)

In addition, one can find: The Apothegms of Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, Enchiridion of Erasmus (103-104), Caprimulge’s Dictionary of the Finnish Language, The Biographical Dictionary of Men who were Born Great, Men who Achieved Greatness, Men Who Had Greatness Thrust upon Them, and Men Who Were Never Great at All (143-146). How disastrous to be in the last category.

Unfortunately, Wimbush’s cynicism and jaded outlook will keep him from the joy of these treasures :” One comes to the great masterpieces of the past, expecting some miraculous illumination, and one finds, on opening them, only darkness and dust, and a faint smell of decay…After all, what is reading but a vice to tickle and amuse one’s mind; one reads, above all, to prevent oneself thinking”(145). Sacrilege, c’est dommage.

May concludes his critical essay with the statement “In writing Crome Yellow, Huxley must have aimed at aesthetic perfection on a small scale. The book itself, rather than anything in it is the positive answer”(39). Huxley was able to make perfection out of things themselves imperfect. “A strain of melancholy is repressed by the intellectual high spirits; the summer mood is unbreeched by forces to which, in its tenuousness, it nevertheless responds”(40).

I loved this little novel, Huxley’s first. It is a great holiday read, a great escape, a great introduction to Huxley’s works of fiction!

Works Cited

Aldous Huxley. Crome Yellow. New York: George H. Doran, 1922.

Keith M. May. Aldous Huxley. Great Britain: Harper & Row, 1972.