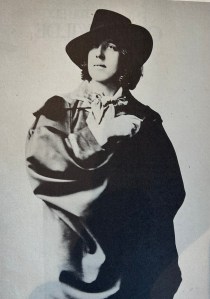

“The world of 1878 became obsessed with the spectacle of an esthetic costume consisting of a loose shirt with a turn-down collar, a flowing green tie, a velveteen coat with a large sunflower in the buttonhole, knee breeches, a beret and long curled hair—“(Strauss, 167).

Do you have a clear mental picture? Obviously, this is a description of an up-and-coming Author, Oscar Wilde, who had just been invited to America for a lecture which was solely based on the “reputation of his costume”, according to the New York Times writer Harold Strauss (1933). This was a “profitable lecture tour”, which paid Wilde enough to “live his beloved life of luxury and idleness for some time thereafter in Paris”(167).

G. J. Renier, a Wilde biographer, saw this obsession in a different light as he states, “Unfortunately, the world was really interested in the tragedy of a witty, maladjusted Irishman who only pursued dreams of beauty and the perfect phrase to conceal their inner turmoil in his soul”. Renier’s chief concern in this biography published in 1933 is not with the details of Wilde’s life nor the circumstances of his writing, but with his personal maladjustment.

For this blog, I will reference Renier’s biography Oscar Wilde: Short Biographies—No. 19.

My Introduction to Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray

Have you read Wilde’s masterpiece, “The Picture of Dorian Gray”? It is a cautionary tale of the dangers of vanity and a hedonistic lifestyle. I first became acquainted with this brilliant story when I saw Ivan Albright’s depiction at the Art Institute of Chicago of Dorian’s decayed and corrupted appearance as his sins accumulated. Albright was commissioned in 1943 to create this painting for the 1945 film adaptation of The Picture of Dorian Gray. It is haunting, grotesque, and its image has stayed with me since my first viewing in 1997. [see link of the artist creating this masterpiece in his studio]. Naturally, I rented (VHS anyone?) this movie soon after and hung on every word that Wilde penned. This is still one of my favorite stories.

Professor of Aesthetics

In Renier’s first short biography, Professor of Aesthetics, he paints a mental picture of the aesthetes of England in the ‘seventies and eighties’: Victorian bric-à-brac, the illuminati, the arrogant Royal Academy, where “Humour is the defence of all-but-mute…the language was studded with irrelevant hyperbole”(3).

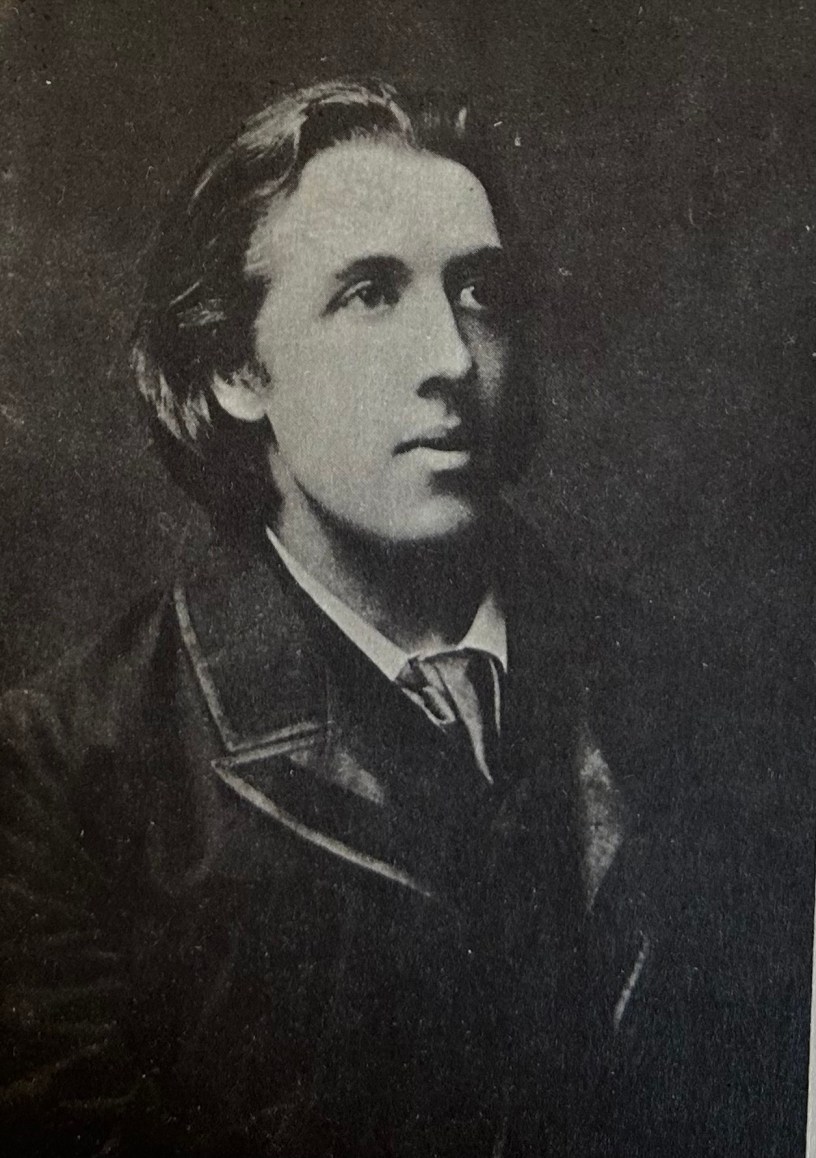

Wilde joined this world in 1878 at the age of 24, fresh from Ireland and Oxford. He obtained a first class in Classical Moderations and in the final class of Literae Humaniores. During his years at Oxford, he also traveled the world spending many days in Italy and Greece studying the Renaissance which influenced his dress, speech, and writing. He published a volume of poems in 1881 (on beautifully printed Dutch hand-made paper bound in white vellum decorated with gold) which echoed Marlowe, Milton, Keats, Tennyson, Browning, Dante, Gautier, and Baudelaire (10).

Shortly after publishing this work of poems, Wilde was invited to America. Renier recounts that “the intelligent and unenlightened came to hear him, expecting different things”(this is obvious from Shaw’s article which I quoted above).

Wilde lectured more than two hundred times and startled Americans when he told them they were not living in the nineteenth century. “The touching and disarming keenness of Americans to know all manifestations of culture was less prominent in those days” explains Renier (15). The Irish from Wilde’s homeland welcomed him in Boston as well as most of his audiences. “Boston was then, as it still is, the most intelligent town in the United States”, claims Renier (in 1933), as its students were more closely akin than those of other institutions to that curious phenomenon of “a mixture of childishness and animal spirits”(16). Following Wilde’s lectures in Boston of his days at Oxford under the leadership of Ruskin, students would burst into vigorous applause. By the charm of his voice and the sheer magnetism of his personality he had tamed a crowd of “Anglo-Saxon adolescents” (17).

Possibly one of the greatest disappointments of Wilde’s American tour was meeting Walt Whitman, whom he had greatly admired. Wilde did not relish the poverty and untidiness of his hero and, likewise, Whitman did not approve of Wilde’s affectation.

At the time of Strauss’s NYT article (1933), there was “no complete and authoritative bibliography of Wilde” (168). That is not the case today as Wilde is one of the most celebrated authors of the nineteenth century,

Work Cited

G. J. Renier. Oscar Wilde: Short Biographies—No. 19. London, Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson & Sons LTD, 1933.

NYTimes Archives: Harold Strauss, The New Life of Wilde, 1933, p.167

https://operasandcycling.com/theatre-montparnasse/

Thank you for sharing your post.