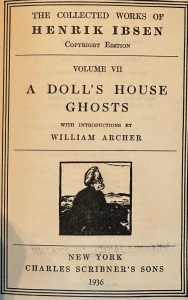

After a deep-dive into the influence of works in Scandinavia by both Longfellow [see post] and Hemingway [see post], I began a new quest of reading literature from Norway. My first stop is Henrik Ibsen. I recently acquired works by Ibsen (1828-1906), a 19th century Norwegian playwright and theatre director, from my university library. I am currently reading Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House”, 1936 edition.

Ibsen’s work is very popular in France and I recently bought a literary criticism of his work Ibsen à Europe: revue littéraire mensuelle from my favorite bookstore and my happy place, Gibert Jeune Librairie, upon the high recommendation of Sebastian, le bibliothécaire.

Ibsen’s International influence

In Ibsen: revue littéraire mensuelle, Maerli states that there is a core in Ibsen’s work that is recognizable in all languages. The core is found in his counterparts such as Sophocles, Euripides, Molière, Racine, Goethe, and Chekhov. It presents itself to us as an enigma, a strict rationality in the description of the world that seems rational. Only a small number of writers and playwrights master this form (Ibsen mensuelle, my translation from French to English, 151).

This core is also seen in A Doll’s House, where Ibsen takes Kierkegaard’s thought seriously and shows in his plots what direction life takes if an idea is pushed, in practice, to its extreme consequences. Life is not alive when an idea governs a human being’s actions down to the smallest detail. Ibsen’s characters are not interesting as psychological figures per se, for on this level one can always find motivations for a character’s actions. It is as “non-psychological figures” that the characters try to burst the framework of human existence (152). They dare to let actions follow thoughts, or rather, action and thought become one. They measure themselves against what they do not understand.

In the Norwegian language, Ibsen exercises a particular hold over the language. But just as much as the language itself, it is his ability to suggest the unspoken between people that makes him a great master. The linguistic dimension often loses, in translation, much of its charm or its rhetorical dangers, but the unspoken emerges just as clearly in all languages. What escapes place and time in Ibsen’s dramas is therefore not the language itself, but what it does not express (153).

Ibsen’s Characters

We see that death becomes the companion of philosophy in Ibsen’s works, according to Maerli. His characters are driven by an idea of vocation that prevents them from taking part in life itself because the idea of vocation prevents love between a man and a woman. Often the woman thinks the man’s vocation is more important than their shared love (153). Consequently, she sacrifices her own happiness so that the man can fulfill his ambitious purpose.

Ibsen makes his characters move in a tension between love and vocation, between devotion and hatred. He pushes them to the limits of life; he makes each individual character risk penetrating those limits. His characters are not tied to the 2nd half of the century. Unlike many of his contemporaries, happiness and unhappiness are related in action. The purpose of tragedy it not to depict human beings and human trials, but to delve into deeds. The character of being can be whatever one wishes, but he will only be happy or unhappy as a result of his actions.

In addition, Ibsen’s characters have human faces that are like masks, hiding monstrous forces beneath the surface, the very forces that, as spectators, we perceive as archetypal traits once we are caught in the action. His characters do not concern the author; they appear as independent individuals (154). “They create their own action within the framework of the action, assigning themselves a goal and having the fierce will to achieve it. To do this, they omit shouting their point, they lie if necessary. It is the action that makes the goal apparent. The other characters do not necessarily believe what is said”.

In addition to death, love, and these strong forces in Ibsen’s texts, Maerli points out that there is a great liberating humor which highlights the tragic and makes it even more tragic (160). Beneath their sinisterly bourgeois exterior, Ibsen’s characters perform profoundly tragic acts that are almost impossible to live with.

Ibsen’s purpose in using humor was to break the shackles of the romantic style which was found in contemporary literature. It used humor to emphasize the plausibility of their actions. Perhaps this aided his characters in not taking themselves too seriously. Ibsen used language as his most important means of rhetorical action to hide his intentions (160). Language becomes not an act but a lie. The action in which Ibsen places the character reveals the lie and forces the character to confess his intentions.

“Ibsen is both luminously clear and obscure. He conducts his plots according to a strict development to the point where one can no longer understand, but on the contrary must intuitively pursue towards ‘the moment’ when everything will be clear without having been explained. Figures emerge in this clarity such as a Falstaff, a Don Juan, an Alcestis, a Tartuffe, etc.”(161).

Ibsen was great in his time. This greatness takes his work out of the 19th century in an uncertain world. His characters belong to an immortal gallery of all time under their own names, and belong to all eras (161).

Work Cited

Terje Maerli. Ibsen in Europe: revue littéraire mensuelle. Paris, Avril 1999. [My translation from French to English in the text.]