I recently acquired an intriguing book, Seen in Germany, which was written in 1901 by Ray Stannard Baker, a historian and American journalist who received a Pulitzer Prize for his biography of Woodrow Wilson.

At thirty-one, Baker traveled to Germany to observe the society, industrialization, culture, and politics during the turn of the century. This is a fascinating look at the day-to-day life of a German citizen pre-WWI, including how they were governed, educated, and perceived by Americans.

Baker starts with the chapter “Common Things Seen in Germany” which considers: the “omniscient Policemen” who are aware of every citizen and their goings on; shops, beer-drinking, the idea of Americans, and Machinery Age.

“The American who travels to Germany soon makes the discovery that he has never known what it really means to be governed”.

Americans have always felt a calm assurance in the superiority of their privilege of having a President, a Governor, a Mayor, a Boss, yet have hardly known that he was governed (3).

In contrast, there is no uncertainty in the Fatherland, claims Baker. The German “enjoys being looked after, and if he fails to hear the whirring of the wheels of public administration, he feels that something has gone wrong”(3).

This impression makes Baker feel wary of being watched during his brief visit. He felt a certain spirit of repression which seemed to pervade the land. With each human movement of activity, Baker questions whether his action was “verboten”. Thus, he warns Americans before their visit to Germany, “Always discover the ‘verboten’ before you are discovered”(5).

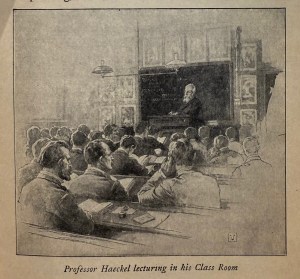

A German Professor : Professor Ernest Haeckel of Jena

My favorite chapter in Seen in Germany is “A German Professor: Professor Ernst Haeckel of Jena”. As a professor with over 25 years, reading Baker’s personal look at the reverent profession in German academia was surprising and aspirational.

“Nowhere in the world is scholarship, especially scientific scholarship, honored as it is in Germany” (134). The very title “Professor” is imbued with honor. In America, as Baker points out, “any man, poor or rich, ignorant or learned, corn-doctor or savant, may append ‘Professor’ to his name, and no one will give him the great honor” (134). Wow, is this still true today, 125 years later? Is being a professor an honored profession, or revered, or respected? In my context, I believe this to be true.

In Germany, once the title of professor is conferred on a man by the government, they are endowed with a chair at a university and are relieved from all financial care and assured a place for life. I guess this would be similar to tenure in the United States.

Baker had the privilege of meeting and interviewing Professor Haeckel, who, along with the distinguished discoverer of the theory of development, A. R. Wallace of England, are the last of the great militant evolutionists. In the mid-eighteenth century, Baker was one of the few thinkers of Europe who supported the theories set forth in the “Origin of the Species”.

Haeckel spent most of his academic life in Jena, Germany, hemmed in by his books, many in German, English, French, Italian, and Russian. Here, in this study, Haeckel wrote his first great work, the “General Morphology of Organisms”, seven years after “Origin of the Species.” His subsequent book, “The Natural History of Creation” has been translated into twelve languages (possibly more today) and contains his monumental works on the Radiolaria, which he regards as “his last and most important contribution to science” (140).

Professor Haeckel’s methods of writing are strenuous and exhausting even to think about. He reached his desk at six o’clock every morning, and he wrote steadily, with a short intermission for dinner, until eight o’clock in the evening. For two months, he was secluded in his laboratory; he wrote no letters and saw no visitors. “One can accomplish much in forty years.”

Baker notes that another thing that impresses one who knows Professor Haeckel is the amount of work he does with his own hands. His writing is all done in pen; most of the pictures in his books are the work of his own brush and pencil; his collections of sea creatures, numbering many thousands, have been made largely by his own hand; and often he has done the preserving and mounting, even writing the labels himself (142).

Haeckel was greatly inspired by the works of the German poets Goethe and Schiller and would walk, almost daily, along the same path where, one hundred years prior, these two great minds would walk, arm in arm. There is a bench with a stone table along this path where Goethe exclaimed to Eckermann, ‘At the old stone table, have we two often eaten and exchanged good and great words’ (144). Schiller wrote his “Wallenstein” in 1798 in this garden.

Goethe saw in imagination the great scheme of life and the developing process of nature when Darwin was a mere boy. “Haeckel would work out the great theory of evolution in the spot where Goethe dreamed it,” observed Baker (145).

I found it interesting that Baker did not discuss Haeckel’s role as a Lecturer, one of the primary duties of a professor in my context. He does provide an illustration of Haeckel lecturing in his classroom. What a privilege for these students to sit under the teaching and scholarship of this great man of science.

Work Cited

Ray Stannard Baker. Seen in Germany. New York: The Chautauqua Press. 1901.