“Peer Gynt is the very incarnation of a compromising dread of decisive committal to any one course.” Ibsen

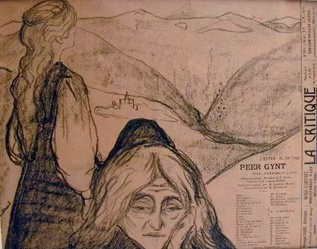

I am on a new quest. I recently discovered works by Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906), a 19th-century Norwegian playwright and theatre director in my university library. I am currently reading Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, 1907 edition.

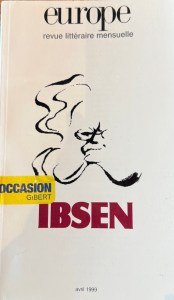

Ibsen’s work is very popular in France, and I recently acquired a literary criticism of his work Ibsen à Europe: revue littéraire mensuelle. from Gibert Jeune Librairie, upon the high recommendation of Sebastian, le bibliothécaire. For this blog, I will be referencing Érik Eydoux’s critical essays from Ibsen à Europe, “La Bataille de Peer Gynt” and Per Tofte’s “Peer Gynt Rentre Chez Lui” (Peer Gynt Returns Home).

I will also be referencing Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite, No.1, Op 46 (I, II, and III) and No. 2 Op 55 (I, II, and III) and request that you stream this masterpiece while reading my blog! I instantly recognized Suite No. 1 Op 46 “Morning Mood” from many Classical playlists and possibly in movie themes.

Peer Gynt

In Peer Gynt, Ibsen takes a resounding break from the national romanticism of his earlier work. In this play, according to Eydoux, Ibsen gleefully castigates Peer, a dreamer and braggart, a symbol of a certain Norwegianness, the man of compromise who never confronts obstacles and refuses any irreversible action (“La Bataille”, my translation, French to English, 99). Since the first performance in 1876, at the Christiania Theatre in Norway, Peer has been elevated to the status of a national hero [note that Eydoux wrote this in 1999—is this still true today?].

It is not obvious in the English translation, but Ibsen wrote the play Peer Gynt from first to last in rhymed verse. Six or eight different measures are employed in various scenes and the rhymes are exceedingly rich and complex. Ibsen uses a frequency of light syllables in Norwegian which gives “double rhymes”. In the Introduction to Peer Gynt, William Archer explains, “the tintinnabulation of these double rhymes gives to most of the scenes a metrical character of ease and simplicity.

In Ibsen’s original text in Norwegian, Act 1 lines 6-10:

Og du skjæms ej for din Moer?

Først saa render du tillfjelds

maanedsvis i travle Aannen,

for at vejde Ren paa Faannen,

kommer hjem med reven Pels,

uden Byrse, uden Vildt; –

og tillslut med aabne Øjne

mener du at faa mig bildt

ind de værste Skytterløgne! –

Naa, hvor traf du saa den Bukken?

[we see the rhyming scheme: a b c c b d e d e f]

English translation from William and Charles Archer:

“Don’t you blush before your mother?

First you skulk among the mountains

Monthlong in the busiest season,

Stalking reindeer in the snows;

Home you come then, torn and tattered,

Gun amissing, likewise game;–

And at last, with open eyes,

Think to get me to believe

All the wildest hungers’ lies!—

Well, where did you find the buck, then?”

Peer Gynt is a boastful, imaginative, and irresponsible young man who lives with his long-suffering mother, Åse. To escape his failures and poverty, Peer invents stories which causes him to be ostracized by his Norwegian community. He soon flees to the mountains and becomes selfish–“to be oneself is enough”, his new-found distorted philosophy, which follows him throughout his life.

Ibsen stated in a letter to Peter Hansen, October 28, 1870, that his own Mother—with the necessary exaggerations—served as the model for Åse “In writing Peer Gynt, I had the circumstances and memories of my own childhood before me when I described the life in the house of ‘the rich John Gynt (Peer Gynt Introduction, X).’”

We find the first of Peer’s first exaggerated adventures in Act I Sc. II:

High ‘oer the ocean Peer Gynt goes a-riding.

Englelland’s Prince on the seashore awaits him;

There too await him all Engelland’s maidens.

Engelland’s nobles and Englelland’s Kaiser,

See him come riding and rise from their banquet.

Raising his crown, hear the kaiser address him—-

In Act III, Sc IV, Peer returns home to find his mother dying:

Oh, life must e’en go as it may go…Alas, Peer, the end is nearing; I have but a short time left.

Peer is in denial. He tries to avoid the imminent calling of his Mother’s death and his irresponsible behavior in being away for so long:

Nay, now we will chat together, But only of this and that,—

Forget what’s awray and crooked, And all that is sharp and sore.

Åse begins to speak of St. Peter inviting her in. Peer addresses St. Peter:

But her you shall honour and reverence, And make her at home indeed . Åse dies. Peer closes her eyes:

Peer closes his mother’s eyes just as the sun dips behind the distant peaks to the west. As young Peer accompanies his dying mother to the threshold of death, we, as readers or the audience, confront our personal relationship with the moment of our own death and of those close to us. The inevitable that we cannot escape, but Ibsen developed the character of Peer to become a source of inspiration for us (163).

Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suites No. 1 and No. 2

In Per Tofte’s essay, we examine the journey of Peer Gynt through the orchestral performance through Edvard’s Grieg in August 1876, at the open-air theater, the Christiania Theatre, Norway, high in the Norwegian mountains. This amphitheater seats almost two thousand spectators around a green expanse of stage surrounding a large mountain lake. The Jotunheim mountain range is the backdrop for this stage highlighted by a majestic sunset behind the blue-tinged, mountain-capped, mountains. [ Grieg later included “Åse’s Death” in Peer Gynt Suite No. 1 (Op. 46), which is why it is now most often heard in concert halls].

The orchestra begins Grieg’s “The Death of Åse” as the deep, calm chords spread across the Dovre mountains (often called Dovrefjell) in central Norway, “bathed in the glow of a nearly extinguished sun”(“Rentre Chez Lui, 162). Ibsen’s contemporary audience would recognize the Dovre as a mythic landscape which is tied to danger and temptation, states Tofte (163).

Grieg poses the question, “Why perform this world-renowned drama in the open-air theatre, amidst the uninhabited mountains of Norway?” (163) It is precisely in the surrounding highlands that the man who served as the model for Ibsen’s character is thought to have lived. The written and oral accounts of a hunter, liar, and braggart named Peer Gynt were acknowledged by Ibsen himself as the source of inspiration for this character (163). Grieg claims that the people who live in Gudbrandsdal, in a community of the Dovre mountains, today, still seem to be closely connected to the figure of Peer Gynt in their imagination. He is experienced as “one of us”.

So, when the play about Peer’s long life was first performed in 1989 in the Gudbrandsdal theatre, the locals felt that Peer had finally “come home”—after a life of constant travel on the world’s stages. The author of this essay, Per Tofte has performed the lead role of Peer Gynt in this amphitheater six times. Tofte states that this role of Peer Gynt is one of the most demanding tasks a Norwegian actor can undertake. He compared it to playing Hamlet in England or Faust in Germany. Playing Peer Gynt was personally enriching and strengthened him greatly as he examined the many vital facets of this character, and the diction of Ibsen’s verse gives the impression of wielding a perfect instrument (164).

Per Tofte was able to play Peer Gynt in the original language of Norwegian. As English speakers, we do not have the privilege of hearing the diction and verse that Ibsen wrote the play. In fact, Ibsen preferred that his play not be translated at all rather than see it rendered in prose. Tofte recommends the English verse structure of John Northam’s magnificent 1993 translation as a benchmark for international audiences who are unable to read the Norwegian text.

At the end of the play, old Peer Gynt returns to the valley of his childhood. He is forced to confront his wasted life. Even though he has traveled widely (North Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean), he does not meaningfully speak other languages in the play. Grieg supposes that, just as Peer exploits, imitates, or dominates other cultures, he does not listen to or belong to them. Linguistically, he remains unchanged—just as he remains morally unchanged (165).

Throughout the play, Peer is always given love, but he never earns it. Before her death, his mother, Åse, tries to teach him how to live a true life– a life of morality and honor. Peer, however, seeks a life of fantasy and grand stories. After Åse dies, Peer finally discovers his true self and asks: “What is it to be oneself? God meant something when he made each one of us.”

Appendix

The story of Peer Gynt occurs in Asbjörnsen’s “Reindeer-hunting in the Rondë Hills”, 1848.

“That Peer Gynt was a strange one, said Anders. “He was such an out-and-out tale-maker and yarn-spinner, you couldn’t have helped laughing at him. He always made out that he himself had been mixed up in all the stories that people said had happened in the olden times (278).”

Film

Charlton Heston stars in his film debut in Peer Gynt, a 1941 amateur 16mm silent movie adaptation of Ibsen’s play for a Northwestern University project.

Work Cited

Edvard Grieg. Peer Gynt Suites 1 & 2. Berliner Philharmoniker-Herbert von Karajan. Deutsche Grammophon (Spotify).

Henrik Ibsen. Peer Gynt.Scribner’s Sons, 1907.

Terje Maerli. Ibsen in Europe: revue littéraire mensuelle. Paris, Avril 1999.