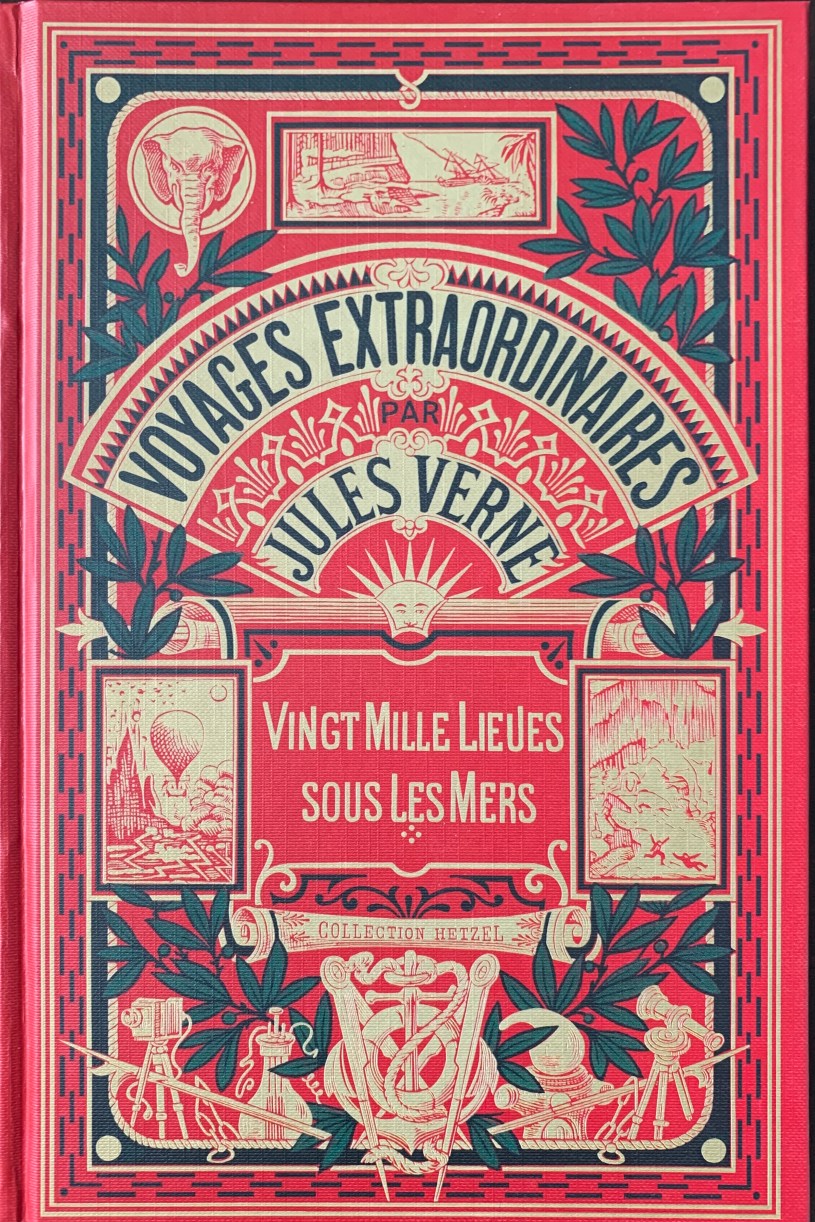

Recently, I discovered Jules Verne’s handwritten manuscript, with his own corrections, of Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea) on Gallica BNF website. What a treasure! I immediately began a quest with my downloaded (and printed) copy of Verne’s manuscript to compare with my French edition of Vingt Mille to discover what changes were made from the original text and why were the changes made.

Much to my dismay, I soon realized that this manuscript, which served as the proofs for his publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel, would not be the same text as the final publication in 1869.

This fact was verified in an article by William Butcher, a scholar who was able to examine two manuscripts of Vingt Mille and compare them with the final publication. As a content editor, my purpose in examining Verne’s original manuscript -the point of view, syntax choice, conceptual intent, content, organization, and writing style in consideration, etc.-was different from Butcher’s scholarship purpose to “determine what Hetzel did not appreciate and what Verne did about it”(43).

Butcher found many discrepancies between Verne’s manuscript and Hetzel’s final publication of Vingt Mille; many which he feels betray the vision that Verne had for his protagonist, Captain Nemo, his relationship with his guest Dr. Arronax, and the voyage of the Nautilus. In fact, Butcher proposes to republish Verne’s novel using a mixture of the original text by Verne with the current publication.

While it was disappointing for me not to be able to personally compare the original manuscript with the published version, I did enjoy learning new truths about this novel from Butcher’s scholarship.

For my readers who are fervid fans of 20,000 Leagues, here are some nuggets from his research.

- Hetzel’s Content of text for publication: While there are commonly disputes between the author and the publisher, it was not for the typical reasons for Verne and Hetzel. According to Butcher, “Hetzel would not allow politics, sex or violence in the books he published” as they were intended for young adult readers (Science Fiction Studies, A Jules Verne Centenary). Verne had no intentions, that we know of, to include sex or violence in 20,000 Leagues, but he did intend to include a political statement showing his dislike of Napoleon III’s government through Nemo’s decisions and subsequent actions throughout the novel.

Secondly, because of Hetzel’s censorship of Verne’s original manuscript detailing the end of Chapter 20, it is unclear if Captain Nemo survives. Butcher points out that as the novel builds to the crescendo of the sinking of the Vengeur off of the Atlantic seabed, the Nautilus was attacked by a warship. Aronnax and his companions escape to the Norwegian coast, but the fate of Nemo is uncertain.

- Nemo’s character and motives: In March 1869, Verne began to submit his closing chapters which Hetzel quickly rejected. Verne had wanted to give Captain Nemo a French or Polish nationality so that: “If Nemo was a Pole whose wife had died under the scourge and children perished in Siberia and found himself faced with a Russian ship, then everybody would accept his revenge [of sinking the ship] (Verne to Hetzel ,May 8, 1869).

Secondly, in the manuscript, Verne originally wrote “ne s’était-il pas attaqué à un vaivire d’une certaine nation qu’il poursuivait de sa haine?”[“had he not attached some ship of a certain nation which he pursued with his hate”]. This line does not exist in the published version. So, the question remains if Nemo’s attacks are against a particular country (48).

Hetzel, in not wanting the Russian government to be upset, remained uninterested in the character arc for Nemo and more interested in the commercial profits. Butcher states that this “is a sad result for Verne’s greatest hero”(47).

Finally, the location of Nemo’s home in the published book is a secret; in Verne’s manuscripts, it is near Tenerife where he is known as “Juan Nemo”. Juan Nemo has an altogether different personality: more independent, intransigent, and a composer.

- Nautilus’ voyage: The original manuscripts had detailed information about the Nautilus’ route to the Arctic as Verne was deeply attached to the waters around Britain. The warship Nemo attacks on this route could be “British, French, Italian or American. The published edition has very little detail (see specifics p.45).

- Arronax: In the manuscripts, Arronax is Nemo’s “prisoner” rather than a “guest”. However, in the novel, the doctor claims the moral right to leave. Since Verne chose to use the present tense to describe Arronax’ own writing process, it is important, therefore, for Arronax to remain in the narrative-he is the narrator, afterall!

Secondly, the Captain’s untoward behavior towards Arronax in the published novel leads most readers, specifically Americans, to see him as a villain. Most European readers, according to Butcher, mistrust Aronnax’s final condemnation and therefore support the Captain’s “freedom-fighter side”(53).

- Captain Nemo’s fate: Butcher concludes his argument with proof from ending of the original manuscript of Verne’s Vingt Mille that Captain Nemo survives and is praised as the ultimate free being. He also found that Nemo supports the French Revolution and Republican ideas and that the ship he attacks in self-defense, is French.

Butcher puts forth the hypothesis of publishing the novel by reinstating the passages lost due to the publisher’s pressure. Is it advisable to “mix and match” earlier, edited versions with the present version? Could one still attach Verne’s name to this new version? Hetzel’s text can no longer be accepted as accurate or authentic, Butchers claims. “We can no longer accept the published version as representing Verne’s original intention”(56).

If this is true, then we must also “debunk” the famous Hollywood “mistranslation of a bowdlerized text(56)”. Wow. Quite a statement, n’est-ce pas?

In the end, even with the editing of a strict publisher, I am grateful for this incredible adventure of the Seven Seas by Jules Verne. I am also grateful that the English translation of Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea made it across the Atlantic Ocean to a Dallas bookstore and into my home as a young girl. I am also thankful for Walt Disney’s vision of creating a High Fidelity 33 1/3 RPM recording of Verne’s “mistranslation” which stirred my imagination and incited my sense of adventure. Here’s to Juan Nemo!

Copyright 2020 by Robyn Lowrie. May be quoted in part or full only with attribution to Robyn Lowrie (www.frenchquest.com).

Works Cited:

Butcher, W. (2005) “The Manuscripts of ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues’”. Science Fiction Studies. Retrieved December 1, 2020 from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4241320

It is indeed sad that Verne did not receive his just due of seeing his work published in the form he intended. Hetzel’s changes were evidently substantial and distorted his intentions.

Thinking back on my own feelings while reading the book (which was at least 40 years ago), the fact that Nemo’s nationality is unspecified could be taken as broadening the book’s meaning by making him, potentially, an avatar of any oppressed people of the time. He might be a Pole carrying out a vendetta against Russia, as Verne apparently intended, but also an Irishman with a vendetta against Britain — or even an Algerian with a vendetta against France (I wonder if Verne thought of that). To the modern reader he could even evoke more current cases such as a Jew fighting back against some Islamic regime or a gay man fighting back against Putin’s. A general principle rather than a specific case.

But of course that’s only one reader’s impression. Verne’s work should have been published as he wrote it. Perhaps someday it will be.

It’s interesting to learn that Hetzel’s edits may have done as much to alter Verne’s stories as some of the poor translations. I can forgive Hetzel more than the translators. He was in the business of creating blockbusters whereas translators are supposed to convey the meaning and spirit of the original text. In Born’s biography, he credits Hetzel’s foresight and keen editorial skills for launching Verne into the spotlight. So overall, I’m grateful for the part Hetzel played.

As you’ve stated, many of these derivative works are still worthwhile and as long as Verne is credited as their originator, I’m fine with them. By the way, I had that Disney album when I was little. My copy is long gone so I sought it out and found it on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r5408wE9q1k

I think it would be fantastic if someone tried to recreate the original version as Verne had intended. Or, produce a mix-and-match version as you’ve suggested. And yes, I think Verne should absolutely be credited as an author (if not “the” author) of the resulting manuscript.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed your posts and hearing your ideas about Verne’s life, books, and legacy. Thanks Robyn.

Good insight Carol. My PoV is from a copy/content editor! I don’t have to worry about the publication side or marketing of a manuscript.

I love the idea of a recreation of the original versions of his stories. Oh, to be young again and pursue this project with funding and access to BNF manuscripts!

My own website ‘Jules Verne and the Heroes of Birkenhead’ will give more information on the origins of Captain Nemo and the Nautilus in the coming months.

Not a French speaker, but I wonder if it should be “attacked” not “attached” in the following:

Secondly, in the manuscript, Verne originally wrote “ne s’était-il pas attaqué à un vaivire d’une certaine nation qu’il poursuivait de sa haine?”[“had he not attached some ship of a certain nation which he pursued with his hate”].

Thank you for a WONDERFUL set of research on Verne!