“The writer is a speaker; he designates, demonstrates, orders, refuses, interpolates, begs, insults, persuades, insinuates. If he does so without effect, he is talking and saying nothing”. –Sartre

Over the twelve years that I have been blogging on myfrenchquest.com, the post with the highest number of visits and interactions is my analysis of What is Literature by Jean-Paul Sartre, written in 2020 [see post].

I was first drawn to Sartre’s perspective of the evolving concept of littérature during the Occupation of Paris while doing a deep-dive into the German occupation of France, particularly Paris, from May 1940 to June 1944. During my research, I read many historical texts and biographies, mostly arguments about what happened, and perspectives of what people recorded after the events. Of course, many historians argue what the facts are as well as how they should be interpreted. Again, this historical perspective could be fifty, one-hundred, or even thousands of years after the events.

Through his writings on the effects of literature during this time, Sartre became a voice of the people, changing French literary culture. Ironically, before the war, Sartre was heavily influenced by German philosophy and created a particular style for his writings which challenged French philosophy and the French language itself (Literary, 167). This, of course, would change over the next decade. According to Priscilla Parkhurst Clark in Literary France:

“The war confronted Sartre with a palpable enemy of a different order than the bourgeoisie…Sartre entered the ‘socialistic’ stage of his life” (174). He was no longer attacking the bourgeoisie as an outsider; he now became an ‘insider’ of French literary culture.

Sartre’s Examination of Writing and Reading

What is Literature is still one of my favorite books, of all time! I reference much of Sartre’s ideas in my courses. Sartre asks these important questions:

“What is Literature? What should and could it be? What aspect of the world do you want to disclose? For whom does one write? What change do you want to bring into the world by this disclosure (37)?”

As a Professor of English Composition, I ask my students these questions, posed by Sartre, at the beginning of each semester. In my English Literature courses, however, the process of writing takes on a different role. One cannot be an effective writer without first being a proficient reader.

Sartre contrasts the role of the reader with that of the writer. I love Sartre’s observation:

“Now the operation of writing involves an implicit quasi-reading which makes real reading impossible. When the words form under his pen, the author doubtless sees them, but he does not see them as the reader does, since he knows them before writing them down (36).”

I consider myself a reader first, a writer second. I had not thought much about the difference between these two disciplines until I read his observation:

“For a writer, the future is a blank page, whereas the future of a reader is two hundred pages filled with words which separate him from the end. Thus, the writer meets everywhere only his knowledge, his will, his plans, in short, himself. He touches only his own subjectivity; the object he creates is out of reach; he does not create for himself. If he re-reads himself, it is already too late. The sentence will never quite be a thing in his eyes. He goes to the very limits of the subjective but without crossing it. He appreciates the effect of a touch, of an epigram, of a well-placed adjective, but it is the effect they will have on others. He can judge it, not feel it (50, 51).”

In addition, Sartre states: “Writing and reading go hand-in-hand. You cannot have one without the other. This is obvious. It is the joint effort of author and reader which brings upon the scene that concrete and imaginary object which is the work of the mind (52).” Cool, cool, cool!!

The Words

I recently found another treasure written by Sartre at my university library. The Words (Les Mots) (1964), is an autobiographical novel that focuses on Sartre’s childhood and early influences, particularly his relationship with books and writing. The work is introspective and philosophical, exploring how he developed his sense of identity and his literary ambitions. The Words is written in two parts: “Reading” and “Writing”. A very fitting companion piece to my previous blog What is Literature.

In Words, Sartre begins with the history of his grandfather Charles Schweitzer, a professor of German from Alsace who played a significant role in Sartre’s upbringing (Albert Schweitzer, the famous theologian, physician, and philosopher, was Sartre’s cousin once removed). After the premature death of his father, Jean-Baptiste, Jean-Paul was raised by his grandfather Charles and his mother Anne-Marie. Charles chose France in 1871 and founded the Modern Language Institute.

Part I: READING

Jean-Paul’s childhood home was filled with many wonderful books. He became familiar with Victor Hugo at a young age by reading “The Art of Being a Grandfather” (one of my favorite books of poems by Hugo to his grandchildren —see my posts] .Unfortunately, Sartre reveals in The Words that he is not a fan of Hugo; in fact, he’s rather critical of Him. C’est dommage.

In addition, Jean-Paul references many Authors who shaped his love for reading:

“Lying on the rug, I undertook many voyages through: Maurice Bouchor, Fontenelle, Aristophanes, Rabelais, Maupassant, Baudelaire, the Larousse Encyclopedia, Voltaire, Corneille, Horace, Homer, Antole France, Goethe, Keller, Flaubert, and Mérimée.

He chose many of these works from a bookshop at the corner of Blvd Saint Michel and Rue Soufflot (which is possibly the same bookshop I have frequented). He preferred “the nonsense of Paul d’Ivoi to Jules Verne, who was too heavy”.

Sartre does, however, give credit to the publisher of Verne’s works: “I adored the series by Hetzel, little theatres whose red cover with gold tassels represented the curtain; the gilt edges were the footlights…I owe to those magic boxes my first encounters with Beauty, when I opened them, I forgot about everything”(73).

I love how he describes the process of reading these adventures: “These stories talked to themselves behind my forehead, between my eyebrows. I gave myself a role in them. They changed nature…I became a hero. I abandoned my family and was assured of living in the best of worlds” (114).

Sartre ends Part I Reading: “I was saved by my grandfather. He drove me, without meaning to, into a new imposture that changed my life”(135).

Part II: Writing

Sartre begins his section on “Writing” with a few facts, as he describes them:

- “Apart from old men who dip their pens in eau de Cologne and little dandies who write like butchers, all writers have to sweat. That’s due to the nature of the Word: one speaks in one’s own language, one writes in a foreign language”.

- “Be self-indulgent, and those who are self-indulgent will like you. Tear your neighbor to pieces, and the other neighbors will laugh. But if you beat your soul, all souls will cry out”(164).

- “One writes for one’s neighbors or for God. I decided to write for God with the purpose of saving my neighbors”(180).

As all good writers, Sartre continued to read veraciously. He strove with cold passion to transfigure his vocation of writing by pouring into his former dreams. “Nothing daunted me. I twisted ideas, I falsified the meanings of words, I cut myself off from the world for fear of comparisons and meeting the wrong people”.

What works inspired Sartre as a young writer?

I have always been drawn to personal libraries, especially of great writers. When we visit historical museums and residences around the world, the first room I want to visit is the Library to see who inspired these great Kings, Presidents, Authors, and Emperors. Napoleon Bonaparte has the most impressive library I’ve seen to date! [see Featured Image]

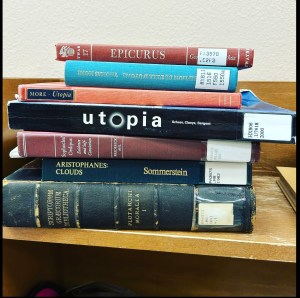

Last year I spent many hours researching Thomas More’s personal library which he “bequeathed” to Utopians in his great novel Utopia. I found that he greatly valued Greek Philosophers and Historians [see post]. So fun!

One of my favorite things about Sartre’s Autobiography in The Words is his recounting of the writers and works that inspired him as a writer even as a young boy including the sacrifices of great writers as : Voltaire and Rousseau had slashed about in their day; Hugo exiled to Guernsey; Zola was jostled and insulted as he defended Dreyfus. Sartre desired immortality through Writing as he sought to achieve greatness and ensure his legacy. His goal was to be considered a literary genius. He talked of writing his name on a manuscript and leaving it to be “found” in his apartment years later and submitted for publication.

Sartre recalls spending many afternoons “dragging his mother to the Seine” to search through the bouquinistes from the Orsay Station to the Austerlitz Station for “yellowed, stained, and dog-eared” books with a strange odor of dead leaves. He amassed a collection of over five hundred books which included: A Crime in a Balloon, The Pact with the Devil, Baron Mousoushimi’s Slaves, and The Resurrection of Dazaar. These books represented heriosm as a perpetual improvisation (216).

Why Write?

In his early years, Sartre wrote to “impress others” rather than writing for purely philosophical reasons, particularly his grandfather. He was driven by the desire for approval, admiration, and recognition rather than a need for self-expression.

As Sartre matured, specifically living through the German Occupation of Paris, he realized that writing is a divine calling of a deep existential realization—meaning must be created rather than discovered (198-199). Sartre believed that he had not chosen his profession as a writer; it had been imposed on him by others: “The grown-ups, who were installed in my soul, pointed to my star; I didn’t see it, but I saw their fingers pointing—I believed in the adults who claimed to believe in me”(207). What an incredible gift to a young man.

These “grown-ups” taught Sartre the existence of the great dead: Napoleon, Themistocles, and Augustus. The intuition of these great men filled him with much joy. His mandate was sealed in this greatness and remained in him throughout his life.

Work Cited

Jean-Paul Sartre. The Words. Translated from French by Bernard Frechtman. New York: George Braziller Publishers, 1964.