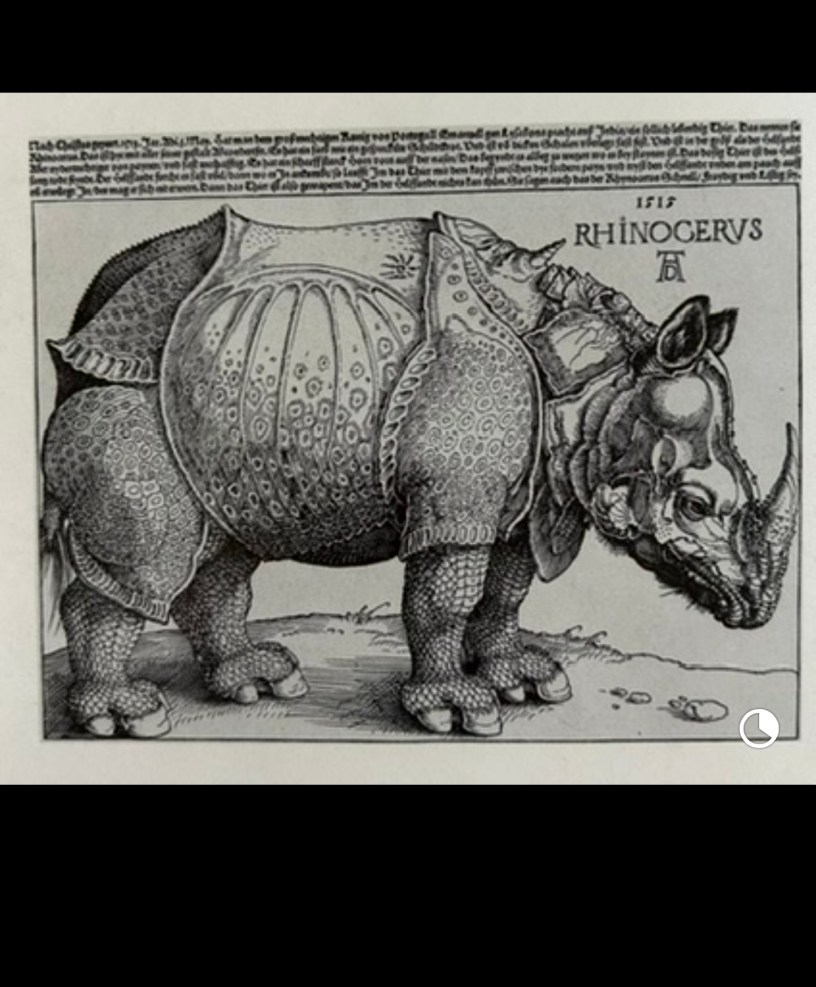

Imagine drawing an animal that you have never seen before. This was the challenge presented to Dürer in 1515, when he attempted to sketch a rhinoceros based on a description which Pliny wrote around 100 BC.

Dürer had never seen this mythical creature with his own eyes as it had been 1,500 years, in the days of the Roman Empire, since the first rhino had been seen in Europe. It was a gift to King Manuel of Portugal from one of his royal governors, who had originally received it from Sultan Muzafar II of Gujarat. Unfortunately, this rare gift drowned off the coast of Italy in a shipwreck. The rhino had been exhibited in Lisbon and was re-gifted to Pope Leo X when the ship was foundered. This caused a sensation in the world of art (Matthew Willis, “Dürer’s Rhinoceros”) .

Dürer portrayed this rhinoceros in his famous woodblock print. He relied on a written description and sketch sent from Lisbon and soon, this image was what Europeans thought of when they imagined a rhinoceros, “largely because it was continuously reproduced in natural histories” (Willis). Conrad Gesner (1516-1558) later borrowed Dürer’s plate of the engraved rhinoceros for his “Historia Animalium” forty years after it was published.

Dürer wrote an inscription in German at the top of the woodcut print largely drawing from Pliny’s account:

“On the first of May in the year 1513 AD, the powerful King of Portugal, Manual of Lisbon, brought such a living animal from India called the rhinocerous. This is an accurate representation. It is the colour of a speckled tortoise and is almost entirely covered with thick scales. It is the size of an elephant but has shorter legs and is almost invulnerable. It has a strong pointed horn on the tip of its nose, which it sharpens on stones. It is the mortal enemy of the elephant. The elephant is afraid of the rhinoceros, for, when they meet, the rhinoceros charges with its head between its front legs and rips open the elephant’s stomach, against which the elephant is unable to defend itself. The rhinoceros is so well-armed that the elephant cannot harm it. They also say that the rhinoceros is fast, merry and jovial”.

Another German Artist Interprets The Rhinoceros

I recently viewed a woodcut print of The Rhinoceros at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, by another German artist from this time, Hans Burgkmair the Elder, who produced a series of 135 woodcuts for the Triumps of Maximillain I under the rule of Maximillian I. Burgkmair’s Rhinoceros looks far more real and lifelike than Dürer’s armored version. Instead of covering the animal with riveted plates and breastplates, Burgkmair shows the hide as heavy, wrinkled, and organic, closer to the texture of an actual Indian rhinoceros.

Where Dürer’s beast feels like a knight in full armor, Burgkmair’s feels almost prehistoric—massive, lumbering, dinosaur-like, with its thick skin, squat legs, and chained stance. He even includes the shackles and lead, reminding us that this was not a mythical creature but a living captive brought to Europe as a wonder.

Burgkmair’s image doesn’t dazzle with fantasy the way Dürer’s does, but it conveys an earthy, animal presence. In some ways, it looks like a cross between a giant reptile and a rhinoceros, a survivor from another age. It is less spectacular as art, which may explain why it never circulated widely, but it feels closer to what Europeans would have seen had they stood before the living animal in Lisbon in 1515.

I am obsessed, however, with Dürer’s whimsical interpretation of a rhinoceros who is “fast, merry, and jovial”–in all it’s armor and glory! With Pliny’s ancient description and travelers’ sketches, Dürer imagined the rhinoceros as if it were an armored knight: plated like a warrior, riveted like a breastplate, almost Attila the Hun-ish in its menace.

To me, this is odd and wonderful—Dürer turned a real animal into a creature of fantasy. He wasn’t mocking it; rather, he was amplifying Pliny’s idea of the rhino as a natural-born fighter, the sworn enemy of the elephant. The result became the definitive “rhino” for Europeans for centuries.

Works Cited

Jesse Feiman. Art in Print, Vol 2, No. 4 (November-December 2012), pp. 22-26

Peter Strieder (1976). Dürer. Verona Italy: Masters Works Press

Matthew Willis. “Dürer’s Rhinoceros and the Birth of Print Media”. JSTOR, June 28, 2016)

Fascinating! I’d seen Durer’s version when I visited the Kunsthistorisches Museum, and it’s always thrilling for me when I finally see an artwork that I’d only ever seen in books before, but if Burgkmair the Elder’s version was there, alas, I didn’t see it.

I am reminded of Herodotus’ and the hippo he’d never seen, and of the early Europeans who were astonished by Australia’s platypus…

Hi Lisa, if you zoom in to the Burgkmair print, you will see his signature, H.B. I had not noticed that either. I thought this was a Dürer when I first saw it. I will have to revisit “The Histories” to read this. Thank you for sharing. Robyn