In 1976, I fell in love with Paris, France after spending just one day in this magical city. In 2004, in order to prepare for a return trip, I began to learn the French language through independent study. My concentric circle of French culture then began to expand to all things art, gastronomy, French history (back to the origines of Gaul), WWII history, and finally the geographical history of France.

When a fellow blogger, WordsandPeace, suggested Graham Robb’s book The Discovery of France on the historical geography of France, I knew this had to be my next read! Robb gives an exploration of France’in which the Sunday Times (UK) says “This book is an elegy to what has disappeared, a retrospective exploration of a lost world”.

In Discovery of France, Robb takes his Frenchquest on a different level. Researching the history and geography of “the forgotten France” took over ten years (four in the library) and 14,000 miles of cycling through the countryside. Robb contrasts “the familiar France of monarchy and republic” with the ancient tribal divisions of Gaul (xv).

Robb refers to several guidebooks to complement his research. Louis Ramond in his guide book Observations faites dans les Pyrénees, (1789) recounts the horrors of a tourist expedition across the Alps of Savoy: “Those people don’t understand their own interests. What tales of trying to reach the Mer de Glace in a carriage”(280)! Jean Ogée’s 1769 guide to Brittany subtitled “Objects that occur Half a League to the Right and Left of the Road”! John Breval’s guide was written for touristes “who can derive pleasure from the barrenest Plain or most uninhabited Village if they only have a date and a name”(281). François Marlin travelled with Robert de Hesseln’s Dictionnaire universel de la France (1771) as it was “useful to have the whole country in six volumes in the pockets of one’s carriage” –Rick Steve’s anyone?

In the first two hundred pages, Robb explores the sociological changes in France from the time of Gaul. This includes the fascinating look at the language and dialects (the standardized French we know today was rarely spoken), migration and commuters, the population explosion after the Revolution, and the restructuring of new departments. I was most intrigued by the developments in Paris and will focus on these chapters for this blog.

In “La Maison du berger”, the poet Alfred de Vigny wrote of his experiences in the new Paris– “the hope of arriving late in a savage place” (216). Vigny lived in a Paris metropolitan apartment a few minutes from several omnibus lines, three railway stations and the Seine. The other parts of Paris were still recovering from the fall of the Roman Empire. One of the best accounts of this transformation of Haussmannian Paris that I have read was David Pinkney’s Napoleon III and the Rebuilding of Paris [see post]. Robb refers to Caroline-Stéphanie-Félicité Du Crest de Saint-Aubin’s Traveller’s Manual for French Persons in Germany and German Persons in France (217).

Tourism

In the mid-eighteenth century, Paris became inundated with touristes, or travellers on the Grand Tour. Most came from England and travelled through France on their way to Florence, Venice, Rome and Naples and would make overnight stops through Paris and Lyon or in the Alps and Pyrenees. Robb references the historian and philosopher Hippolyte Taine in his description of these first touristes: “Long legs, thin body, head bent forward, broad feet, strong hands, excellently suited to snatching and gripping. It has sticks, umbrellas, cloaks and rubber overcoats…It covers the ground in an admirable fashion”(278). [I would love to read a Parisian’s impression of my first visit to Paris in 1976 with a church youth choir dressed in white polyester pants and a rainbow blouse!].

Can you imagine this incredible voyage today? Let’s start in London, why not. Travel by train across southern England, take a ferry across La Manche—or English Channel–with the views of the Normandy coast, the cliffs at Étretat, and dock at Le Havre. Now, using our Eurail Pass, lets board SNCF and travel through Rouen (a three hour tour is a must) and spend at least three days in Paris. Back on the train at the Gare d’Austerlitz and travel across Bourgogne Franche-Compté, Auvergne-Rhône Alpes, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azure and finally to Milan, then Rome. Of course, we will vary the course on the way back home to Geneva, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Grand Est to Dunkirk and back to Dover, England. Ah, so nice!

Back to our Discovery of France!

Before the Revolution, the sights of France that most people came to see could be summarized in a short list: the squares and monuments of Paris and the nearby châteaux of Fontainbleau, Versailles and Chantilly.Robb references the Itinéraire des routes les plus fréquentées (1783) which recommended a year’s stay in Paris followed by ‘two or three weeks in some of the principal towns’ in order to know France and the French (283).

On the other hand, Joseph Lavallée, in his guide book Voyages dans les départments de la France, wanted to show those ‘snooty Parisians’ that the provinces were just as interesting as the ‘bloated capital’. In his travel guide, Lavallée redefines the sights that a patriotic tourist should want to see: instead of ‘gloomy old cathedrals’, he praises factories, public promenades and new housing developments (285). While I do not agree whole-heartedly with this recommendation, I do agree with him that ‘natural beauty and historical interest are a part of a nation’s wealth.

After the fall of Napoleon, curiosity and exchange rates brought huge numbers of tourists to Paris. Some of the most renowned tourists during this time include the painter J.M.W. Turner who sketched scenes along the Seine and the Loire, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who toured Paris and the Loire valley talking to peasants in the vineyards. Longfellow wrote ‘The reality of many a day-dream of childhood, of many a poetic revery of youth, was before me. I stood at sunset amid the luxuriant vineyards of France’(287).

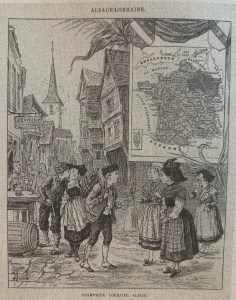

Western France also became a popular region for tourists as the Alsatians retained their native dress of black bows, red skirts and large aprons. Strasbourg, the capital of the ‘lost province’ of Alsace. My ancestors lived in Strasbourg during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries under French government as well long periods under German occupation. In 1871, Alsace was annexed to the new German Empire following its victory in the Franco-Prussian War until 1918, after Germany’s defeat in the First World War.

Paris also attracted many writers during this time. Arthur Rimbaud, Émile Zola, Honoré de Balzac and Gustave Flaubert moved to Paris and began to write provincial literature which underlined the prestige of Paris. George Sand sponsored some of these provincial poets in order to ‘preserve their provinciality’ and rid them of highfalutin language and fancy images (307).

Robb does not include the Impressionists of Paris in the historical geography, which is understandable. There are hundreds of books written about this delicious, aesthetic history of France. He ends his journey with the Verdon Gorges which were revealed to the world in 1906. He includes in this chapter the history of cycling races, highlighting the Tour de France.

As of his writing in 2007, towns and cities in France are still being discovered and tourism is still on the rise, despite the Covid pandemic of the past two years. The Discovery of France—a rich journey for all who partake!

Word Cited

Robb, Graham. (2007) Discovery of France: A Historical Geography. New York: Norton & Co.

Thanks for this wonderful and detailed presentation of the book. I need to reread it!

I’m so glad you spotlighted it on your page! Have a great weekend.

I bought this book a couple of years ago after reading Robb’s Parisians. He packs so much information into his chapters. I’ve had difficulty committing to reading it. Your review is motivating me to dive in.

Hi Carol, much of Robb’s information was new for me and not typically found in French history books I’ve read. For example, Robb states that most historical documents reveal the lifestyles and biographies of the rich, educated, clergy etc. Therefore we know very little of life in rural, working class which made up most of France’s population. Secondly, I had not thought of France as being a rest stop for early travelers heading to Italy and Spain. Things are definitely different in the prime destinations today! ( perhaps just for me!!)

Sounds great.

“A year’s stay in Paris followed by ‘two or three weeks in some of the principal towns”

From far away Australia, this sounds like heaven!