The next Author on my list from Thomas More’s personal library in Utopia is Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a collection of unrelated stories from 8 CE told in chronological order from the creation or nadir of the world to the death and deification of Julius Caesar, the denouement of metamorphosis.

Ovid uses these stories to show the transformative power of love, loss, and grief. In many of these stories, the characters are transformed physically or emotionally through the intervention of gods, the uncontrollable power of desire, or natural causes of time.

In Ovid’s world, everything is fluid—nothing stays the same for very long. Sound familiar? Yes, of course. This has been the pattern of civilization since he created these stories in the 8th century. Ovid’s works have inspired all the great authors: Dante, Chaucer, and Shakespeare–It’s hard to read Pyramus and Thisbe without thinking of Romeo and Juliet.

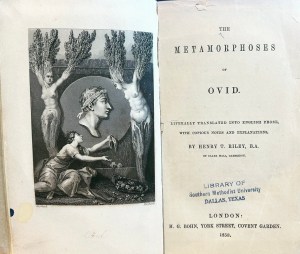

For this blog, I am referencing a very fragile 1858 edition The Metamorphoses of Ovid: Literally Translated into English Prose, with Copious Notes and Explanations, by Henry T. Riley, B.A. of Clare Hall, Cambridge. Much appreciation to the SMU Fondren Library for loaning this treasure from your Permanent Collection!

My favorite part of reading these timeless stories has been in learning the origin of recognizing characters and references from: Narcissus/Narcissism; Pyramus and Thisbe/Romeo and Juliet; Pygmalion/My Fair Lady; Apollo, Diana, Orpheus/Greek gods and goddesses; Arachne/Latin term for spiders; Jupiter, Andromeda, Europa, Venus/Astrological names.

In addition, even though Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Homer’s Iliad and The Odyssey belong to different periods of ancient literature and traditions, the common gods I found that are featured in these works are: Jupiter/Zeus, Neptune/Poseidon, Apollo, Venus/Aphrodite, Mars/Ares, Mercury/Hermes, and Diana/Artemis. Homer’s works influenced the Greek culture and Ovid’s the Roman culture.

Metamorphoses has inspired many works in literature, sculpture, painting, and music. It still influences today!

I chose to highlight Daedalus and Icarus in this post [the story is included at the end].

Daedalus and Icarus

Daedalus was an architect and inventor who, along with his son Icarus, was exiled by King Minos to the island of Crete after the King feared that Daedalus would reveal secrets of the Labyrinth that he was commissioned to build.

Daedalus and Icarus were surrounded by the sea with no possible way of escape. This loving father did not want this fate for his beloved son, so he created two pair of wings out of feathers for them to “fly” away.

I love the special care that Daedalus gave these wings for his son. Ovid gives the details of them: He arranges feathers in order, beginning from the least, the shorter one succeeding the longer, in an incline, as any rustic pipe prom straws unequal slants. He bound with thread the middle feathers, and the lower fixed with pliant wax; till so, in gentle curves arranged, he bent them to the shape of birds.

Daedalus gave a specific warning to Icarus before the flight:

“My son, I caution you to keep the middle way, for if your pinions dip too low the waters may impede your flight; and if they soar too high the sun may scorch them. Fly midway. Gaze not at the boundless sky, far Ursa Major and Bootes next. Nor on Orion with his flashing brand, but follow my safe guidance (Book VIII. 183-189).”

“Amid his work and admonitions, the cheeks of the old man were wet, and the hands of the father trembled”. Wet with sweat, tears? Were his hands trembling due to fatigue or fear of the risk they were taking?

Can we just pause the story here, please? Can we just take a moment with this beautiful visual of Daedalus and Icarus floating through the azure blue sky (no clouds on this day of freedom) above the Mediterranean Sea of vibrant turquoise and dark blue hues, over the deep waters, and emerald greens near the shores bordered by foamy breakers.

Imagine the exaltation in the father’s heart that he has created a plan of escape for his son. They fly over Samos, Juno’s sacred isle; Delos and Paros too; on the right Lebinthus and Calymne.

Icarus, excited by the newfound freedom and sensation of flying, ignored his father’s warnings and soared higher towards the sun. The heat melted the fragrant wax that held his plumes.

“He waved his naked arms instead of wings, with no more feathers to sustain his flight. And as he called upon his father’s name his voice was smothered in the dark blue sea, now called Icarian from the dead boy’s name.”

Daedalus, “not a father”, called “Where are you Icarus…in what place shall I seek you, Icarus? “He saw the wings of his dear Icarus, floating on the waves; and he began to rail and curse his art. He found the body on an island shore, now called Icaria, and at once prepared to bury the unfortunate remains” (221-235).

There are many interpretations and themes of Ovid’s cautionary tale.

Who was at fault? The Father for being too ambitious in planning a harrowing escape for he and his son from the island of Crete? The imprisonment of the labyrinth could have also led to an untimely death for the Father and the son so the risks were perhaps justified. The flight of Icarus is often used in literature as a metaphor for ambition and the pursuit of dreams.

Or was the hubris of young Icarus at fault for not heeding his Father’s advice? This was his first attempt at “flying” with man-made wings so it is possible that his arms could have tired, or he could have been swept up by a strong wind which would have resulted in a perilous death. In addition to the central theme of the Father-Son relationship, the theme of tragedy is also common in Greek mythology and serves as a reminder of the unpredictability of fate and the inevitability of mortality (Ovid, 265). We see here that descent is used as a metaphor for disobedience.

At the end of Daedalus and Icarus, Riley includes this explanation:

“Daedalus was a talented Athenian, of the family of Erechtheus; and he was particularly famed for his skill in statuary and architecture. He became jealous of the talents of his nephew, Talos, whom Ovid here calls Perdix; and envying his inventions of the saw, the compasses, and the art of turning, he killed him privately. Flying to Crete, he was favourably received by Minos who was then at war with the Athenians. He there built the Labyrinth, as Pliny the Elder asserts, after the plan of that in Egypt, which is described by Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, and Strabo. Philochorus, however, as quoted by Plutarch, says that it did not resemble the Labyrinth of Egypt, and that it was only a prison in which criminals were confined.

Minos, being informed that Daedalus had assisted Pasiphaë in carrying out her criminal designs, kept him in prison; but escaping thence, by the aid of Pasiphaë, he embarked on a ship which she had prepared for him. Using the sails, which till then were unknown, he escaped the galleys of Minos, which were provided with oars only. Icarus, either fell into the sea, or, overpowered with the fatigues of the voyage, died near an island in the Archipelago, which afterwards received his name. These facts have been disguised by the poets under the ingenious fiction of the wings, and the neglect of Icarus to follow his father’s advice, as here related” (274).

Work Cited

Henry T. Riley. The Metamorphoses of Ovid. H.G. Bohn, York Street: Covent Garden, 1858.

DAEDALUS AND ICARUS

[183] But Daedalus abhorred the Isle of Crete—and his long exile on that sea-girt shore, increased the love of his own native place. “Though Minos blocks escape by sea and land.” He said, “The unconfined skies remain though Minos may be lord of all the world his sceptre is not regnant of the air, and by that untried way is our escape.” This said, he turned his mind to arts unknown and nature unrevealed. He fashioned quills and feathers in due order—deftly formed from small to large, as any rustic pipe prom straws unequal slants. He bound with thread the middle feathers, and the lower fixed with pliant wax; till so, in gentle curves arranged, he bent them to the shape of birds. While he was working, his son Icarus, with smiling countenance and unaware of danger to himself, perchance would chase the feathers, ruffled by the shifting breeze, or soften with his thumb the yellow wax, and by his playfulness retard the work his anxious father planned.

[200] But when at last the father finished it, he poised himself, and lightly floating in the winnowed air waved his great feathered wings with bird-like ease. And, likewise he had fashioned for his son such wings; before they ventured in the air he said, “My son, I caution you to keep the middle way, for if your pinions dip too low the waters may impede your flight; and if they soar too high the sun may scorch them. Fly midway. Gaze not at the boundless sky, far Ursa Major and Bootes next. Nor on Orion with his flashing brand, but follow my safe guidance.” As he spoke he fitted on his son the plumed wings with trembling hands, while down his withered cheeks the tears were falling. Then he gave his son a last kiss, and upon his gliding wings assumed a careful lead solicitous. As when the bird leads forth her tender young, from high-swung nest to try the yielding air; so he prevailed on willing Icarus; encouraged and instructed him in all the fatal art; and as he waved his wings looked backward on his son. Beneath their flight, the fisherman while casting his long rod, or the tired shepherd leaning on his crook, or the rough plowman as he raised his eyes, astonished might observe them on the wing, and worship them as Gods.

[220] Upon the left they passed by Samos, Juno’s sacred isle; Delos and Paros too, were left behind; and on the right Lebinthus and Calymne, fruitful in honey. Proud of his success, the foolish Icarus forsook his guide, and, bold in vanity, began to soar, rising upon his wings to touch the skies; but as he neared the scorching sun, its heat softened the fragrant wax that held his plumes; and heat increasing melted the soft wax—he waved his naked arms instead of wings, with no more feathers to sustain his flight. And as he called upon his father’s name his voice was smothered in the dark blue sea, now called Icarian from the dead boy’s name. The unlucky father, not a father, called, “Where are you, Icarus?” and “Where are you? In what place shall I seek you, Icarus?” He called again; and then he saw the wings of his dear Icarus, floating on the waves; and he began to rail and curse his art. He found the body on an island shore, now called Icaria, and at once prepared to bury the unfortunate remains.

[236] But while he labored a pert partridge near, observed him from the covert of an oak, and whistled his unnatural delight. Know you the cause? ‘Twas then a single bird, the first one of its kind. ‘Twas never seen before the sister of Daedalus had brought him Perdix, her dear son, to be his pupil. And as the years went by the gifted youth began to rival his instructor’s art. He took the jagged backbone of a fish, and with it as a model made a saw, with sharp teeth fashioned from a strip of iron. And he was first to make two arms of iron, smooth hinged upon the center, so that one would make a pivot while the other, turned, described a circle. Wherefore Daedalus enraged and envious, sought to slay the youth and cast him headlong from Minerva’s fane,—then spread the rumor of an accident. But Pallas, goddess of ingenious men, saving the pupil changed him to a bird, and in the middle of the air he flew on feathered wings; and so his active mind—and vigor of his genius were absorbed into his wings and feet; although the name of Perdix was retained. The Partridge hides in shaded places by the leafy trees its nested eggs among the bush’s twigs; nor does it seek to rise in lofty flight, for it is mindful of its former fall.

[260] Wearied with travel Daedalus arrived at Sicily,—where Cocalus was king; and when the wandering Daedalus implored the monarch’s kind protection from his foe, he gathered a great army for his guest, and gained renown from an applauding world.

Thanks for sharing this idea. I follow your blog but can you follow mine. Anita

Thanks for sharing this idea Anita